Disclaimer: Hundreds of thoughts went through my head as I watched the fallout, debate and outrage over the events in Ferguson. I think, like many others, I needed time to process and see things more clearly. I have no properly founded stance on who is guilty of what crime, and only endeavour to share my perspective on the situation.

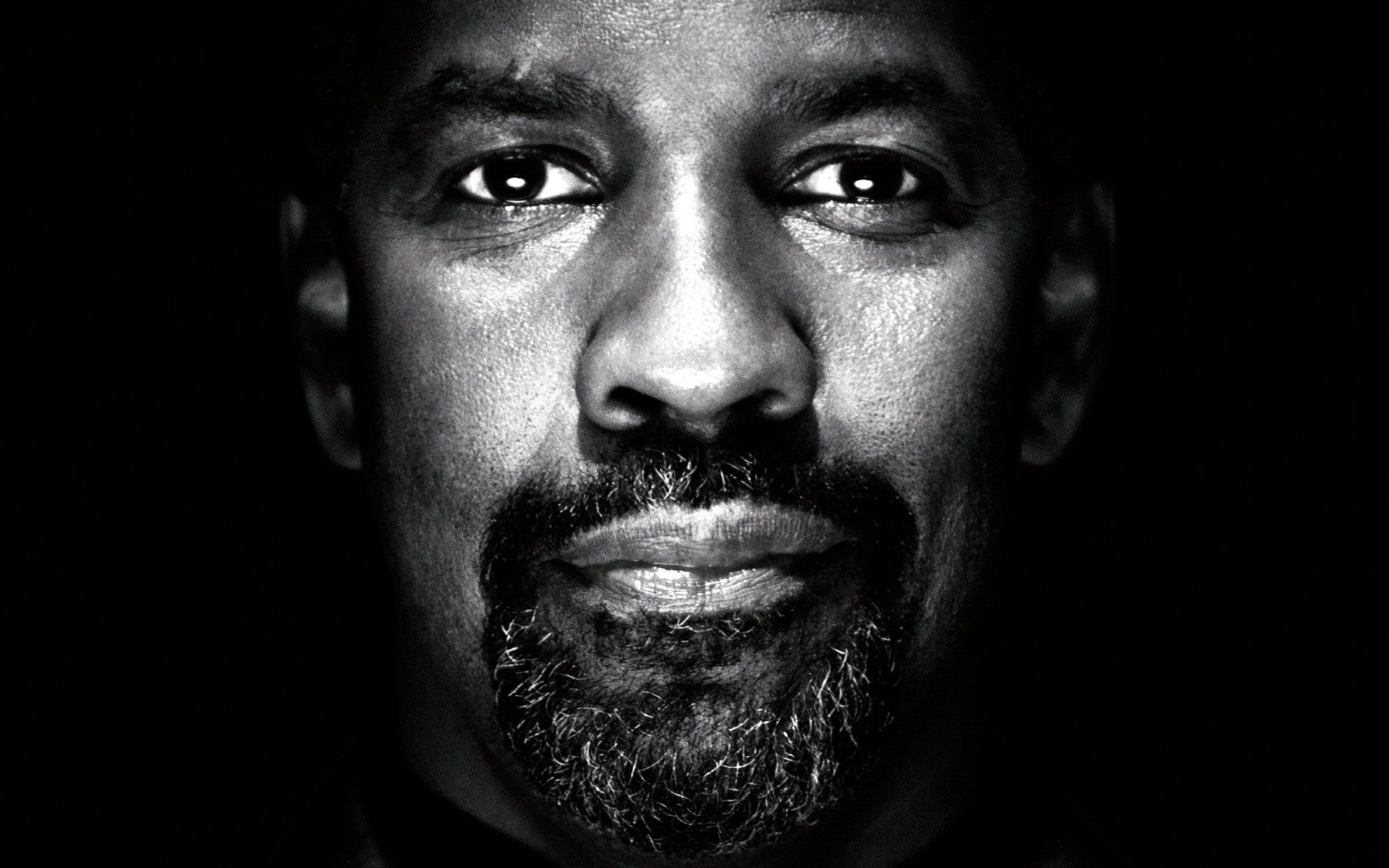

I was born a black, Southern Baptist male in South Carolina. As I grew I was simply more thoroughly defined. I grew to hate the fact that I was not only black by DNA, but also “black” by stereotype.

I was athletic.

I had the humble beginnings of an afro.

I liked rap.

I could dance/had rhythm.

By themselves, none of these things really meant anything. But in other people’s eyes, intead of rounding out my individuality, they became reason after reason to fade me into a false concept of a “black male”. I have rarely been the person to do the contrary thing just because it was contrary. I listen to rap because I admire the wordplay, not because I’m supposed to like it. I was only good at sports after considerable effort. Yeah, some of it came naturally, but more from developed skills than talent.

It was amusing back then. I related to Turk from Scrubs in a very strong way. Going to a predominantly white school, I felt like a fake (whatever the hell that means) and had an intermittent sense of feeling out of place. I was lucky enough to realize early on that my personality also contributed to this. Introversion made me feel a bit distant even in situations where, for melanin-related reasons, I should have felt comfortable. I guess in the end, I am one of those people fortunate enough to possess just enough adaptability to be accepted by many different groups, and enough independence to not regret never being a permanent member.

This was equal parts angering and amusing. I definitely didn’t complain when my fabled “quick-twitch” muscles meant I could outrun and out jump most people of the same height. I shrugged off being followed around in nice stores or getting “special attention” because compared to the horror stories I had heard, this was barely racism. I’d seen Glory.

Couldn’t bring myself to use a real picture from the movie. Just watch it.

I was shaken, though, when some of my extended family asked: “Why do you act so white?”. In honest curiosity, I asked what I did that was so un-black, and their response was “Well, you talk good.”

![]()

My parents did an incredible job of shielding me from the worst of racism until I was old enough to begin to understand it. What they could never separate me from were the expectations. As I said, athletic, rap fan, dancer, afro. Innocuous. “It’s just cause you’re black.” Yeah, you’re jealous.

Many of those things felt like appeals to, or comments on, what was already a part of me. Just innocent questions. But then they slowly became tests. It was harmless enough to see a sitcom make fun of the black guy who couldn’t dance, and the shock when Stanley couldn’t play basketball. But now in the post-Jim-and-Pam era, it’s both amusing and terrifying to see what other expectations the broad brush of being “black” creates.

***

It was pretty obvious that when the facts came in, the only two that mattered in most conversations about the Michael Brown and Eric Garner cases were the races of those involved.

Every sentence that started with “As a black man…” or “As the first black president…” said on a much larger scale the same thing as the kids in middle school:

“I already have you and the situation figured out.”

“I already know enough about people like you to justify my behavior”

“This decision was made for you long ago, before you even knew it.”

“I dare you to betray my image of you.”

Now, of course, stereotypes are not only natural but one of the biggest reasons we as a species are alive. But much like the internet, Jagermeister, freedom of speech and buffets, we are prone to misuse them. Not enough people are taking serious time to play devil’s advocate to the hardwired, predetermined and unenlightened prejudices and (here we go) virtues that we hold so dear.

We want to wrap it up nice and neat with a bow…

If we watch a debate on religion, we want to know which religion won.

We want to find the fact that PROVES something right or wrong. Forever.

That first 30 seconds of a song doesn’t just tell you the song is bad, but that the singer can’t sing, the album must be crap, and the song is the worst thing since dentists.

That pastor who got caught is a good man one day, and a demon the next. Not just a broken man.

And that white cop who killed a black man could not possibly be justified because a different white cop did something similar to a different black man before and he was found guilty.

Your opinion on _______ is ________ because you’re black.

Period. Full stop. On to the next story.

![]()

It’s no wonder that the hardest words to say in any language are “I am sorry.” And I think the words”I am wrong” are a close second. When we were kids, we instinctively knew that learning and growing was a continual process of being proved wrong. It’s when we choose a side and fight to fortify it that questions become attacks and doubt becomes betrayal.

At this point, even the simple act of admitting “I COULD be wrong” would be not just a leap, but a head-long sprint in the right direction.

Recent Comments